INTRODUCTION

ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE. EVEN THE IMPOSSIBLE.

That is the paradox of our times, and our politics. In California, in the U.S., and in democratic societies around the globe, we the people talk often about how hard it is to get anything done. We talk about all the limits and constraints.

We express frustration with political gridlock. We say that all politicians are hopeless partisans, and must appeal to their base. We recite the wisdom that democratic governance is about slow, incremental change. We offer nostalgia for the New Deal and the post-war era when big things happened fast. We rue how hard it is to get our disengaged citizenry to pay attention to politics and government. But if that is true, what explains the recall—and all that has happened since?

How do we explain a political earthquake that shook not just California, but made news in every country on earth? How can we explain a historic event—the sudden replacement, by vote of the second most powerful elected official in the United States, the most powerful country on earth? How can we account for the one-of-a-kind governor—a movie star muscleman immigrant— who had never been elected to high office before, and hasn't been elected since?

How can we begin to understand its ongoing impact?

By throwing away our conventional wisdom, and looking squarely at the recall again. If we do, we might see that we are wrong about politics, about government, and about ourselves. The recall was a big thing that did get done. Attempts to stop it and limit it went nowhere. The recall cut through gridlock. It happened fast, lightning-fast, in just 60 days. And it got the public's hard-to-get attention. And news of it was followed, according to one poll, by 99 percent of Californians, and it drew news coverage in every country on earth.

And it surprised virtually everyone working in media and politics.

But now, a generation after the October 2003, the same pundits who once dismissed the prospects of the recall now dismiss its impact. They will tell you that the recall didn't fulfill its promises, that it didn't lead to a revolution, that it didn't take money out of politics, or push out the special interests and put the people back in control of government.

But I’ll tell you something about those pundits, because I was one of them. We’ve gotten old.

And so, we’re forgetting all that happened in the recall—and all the changes that the recall inspired in our state and in our country. In retrospect, the recall looks like the first, and strongest, of the 21st century election earthquakes that have shaken the world. Only Brexit comes close in impact.

The recall would also resemble, in some ways, the elections of Barack Obama and Donald Trump. Like Arnold Schwarzenegger’s recall victory, the triumphs of those two presidents had seemed impossible. Like the recall victory, the elections of 2008 and 2016 brought politically inexperienced outsiders into office. Like the recall victory, the triumphs of Obama and Trump would unleash changes in our country and our world that almost no one had predicted. For Americans, the recall was a preview of how our politics would change, and grow louder, more contested, more populist, more direct. For Californians, the recall was something more: the beginning of a new era in governance.

Indeed, if we look back with clearer eyes—if we recall the recall better— we are likely to be surprised at how much that very special election has changed us, and is still changing our governance and our democracy.

California governance is a matter of global import now. Our governorship has become a second American presidency, and the state a second American republic. California governors are seen as counters to whomever holds the White House; they even have foreign policies. As a result, our state government is ever more powerful, issuing policies that are copied in other states and other countries.

Having invested that much power in our leaders, we Californians expect direct action now. Direct action was what the recall, and the winner of the recall election, both embodied. And after our 20 years, we hunger, even more than before, for direct action.

The recall is an event in our past. But its history tells us where we are now, and offers glimpses of our future.

Reading the below text, you might conclude that the recall isn’t over. Because the story still has the power to change us.

And because—when it comes to matters of change and California and Arnold Schwarzenegger—anything might be possible, even you-know-what.

THE DECISION

Arnold Schwarzenegger left early for the taping of

“The Tonight Show” on Wednesday afternoon,

August 6. It was a case of traffic, not nerves.

Outwardly, he seemed at ease. At the studio, he

was greeted by three consultants who had been

handling press questions.

Arnold Schwarzenegger left early for the taping of

“The Tonight Show” on Wednesday afternoon,

August 6. It was a case of traffic, not nerves.

Outwardly, he seemed at ease. At the studio, he

was greeted by three consultants who had been

handling press questions.

One consultant, George Gorton, had a copy of a statement from Schwarzenegger announcing he would not run in the October 7 election to recall Governor Gray Davis. Instead, he would endorse former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan. The document is fine, Schwarzenegger told his aides. But don’t give it to the press until after the show.

Minutes before he was to go on stage, he still had not decided whether he was running for governor.

The entire world expected to Arnold Schwarzenegger not to run, because that’s what his team of political strategists was telling people. And because everyone knows that political strategists are the experts and thus run the biggest campaigns. It’s considered impossible for a novice candidate to run his own campaign, make his own decisions, and keep his political advisors in the dark.

But this was Schwarzenegger, for whom the impossible could be possible. His whole life— poor kid from small Austrian town who became a champion bodybuilder, movie actor, Kennedy in- law and one of the most famous living beings on earth—had convinced him that anything is possible.

Former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan and Schwarzenegger lived a little more than one mile apart in Brentwood. It was a supreme irony that of all the potential beneficiaries of the people’s revolt that Sacramento anti-tax activist Ted Costa had launched with his recall petition back in January, these two rich men stood to gain the most.

Neither Riordan nor Schwarzenegger had given the improbable recall significant assistance in its improbable path to qualifying for the ballot. They were mainstream figures who read the mainstream press, including my then-employer, the Los Angeles Times, which kept reporting that it would never qualify.

And yes, Ted Costa, who worked out of a former roller derby rink in suburban Sacramento, had told a Bakersfield political consultant, “This would be perfect for Arnold” as he launched the petition campaign. But Costa and Schwarzenegger had never met.

“This would be perfect for Arnold.”

Instead, it was largely unknown men and women, mostly outsiders on the political right- wing, who had gotten the measure qualified. Among their names were Sal Russo, Howard Kaloogian, Mark Abernathy, David Gilliard, Ray Haynes, Roger Hedgecock, Tom Bader, and Phil Paule. They had gotten a quiet, unseen push from a powerful Democratic interest group, the California Teachers Association, which had battled Davis so often that it had polled on the question of recalling the governor—and then leaked the poll’s broad support for a recall to a Republican strategist.

The recall activists on the right had overcome huge obstacles. When Democrats tied up all the signature gathering firms, hiring them for other initiative petitions so they could not circulate the recall petition, the activists dug up a down- and-out petition circulator in Missouri and brought him out to Orange County to build a statewide signature operation. They convinced a San Diego-area Congressman named Darrell Issa to provide millions from his personal fortune to make the signature gathering possible. And they persevered in the face of the scorn of the media, the skepticism of their fellow Republicans, the persistent attacks of the incumbent governor. All the skepticism and the scorn were justified. The guys behind the recall hadn’t won much in politics. And while the tool of the recall had been a part of politics for nearly a century, and had been used frequently at the local level, no statewide elected official had ever been recalled in California. In fact, just one governor in the history of the United States—Lynn Frazier of North Dakota—had been removed from office in this way, and that was back in 1921.

But Californians were unusually angry and frustrated at governmental dysfunction. The state budget was constantly in crisis. An energy crisis had produced rolling blackouts, and then sky-electricity bills. Governor Davis had won re- election in 2002 despite these problems, but very narrowly and only because of the weakness of the Republican opponent.

The recall qualified, over the Fourth of July weekend. Just as Schwarzenegger’s new film, Terminator 3, was opening in movie theaters.

In July 2003, a newspaper poll showed Riordan to be the first choice of voters to replace Davis, with 21 percent of the vote. Schwarzenegger was second, with 15 percent. If both ran, they could harm each other. If they joined forces, they would control a center bloc large enough to triumph in a multicandidate race.

Beginning July 23, the day after Schwarzenegger returned from a tour for Terminator 3, the star and the former LA mayor met or talked every day. The deadline for candidates to declare themselves for the October 7 election was Saturday, August 9. Schwarzenegger told political associates he wanted to back Riordan. But in their conversations Riordan was wavering, saying he needed more time to put a team together.

In the midst of this, Schwarzenegger booked himself on “The Tonight Show” for August 6. — Acting for the first but not the last time as his own campaign manager, he did not consult with his political advisors on the decision. Since Schwarzenegger had given every indication that he wasn’t running, the advisors thought that the show offered a great venue to talk up the recall and Riordan.

The advisors had not known Schwarzenegger for long, but they had known him long enough to understand that he was always full of mystery when it came to big decisions. For more than a month, he had been sounding out his worldwide network of friends and business associates. He even took the temperature of his lifelong Austrian friends. Peter Urdl, his elementary school classmate and the mayor of his hometown of Thal, said he warned Schwarzenegger that “in politics you cannot pick your roles. If you do it, you’re going to see what kind of bullshit you have to deal with.” In Schwarzenegger’s mind, the question was not merely whether to run for office or not. This may have been the ultimate Schwarzenegger bake- off: he appraised the future of his movie career, his investments, and his charitable enterprises. Through this methodical yet flexible style, he found he had no shortage of options.

New Line wanted him for a comedy, Big Sir, about a man traveling cross- country with his future stepchildren. There continued to be talk of sequels, True Lies 2 or King Conan. And he was still in the midst of transforming his national Inner City Games charity into a provider of after-school programs. As always, he had an abundance of business opportunities.

There was another factor to consider. It seemed inevitable that allegations of womanizing that had appeared in the tabloids and entertainment press in 2001 would resurface. Polling conducted both for Schwarzenegger and for Democrats showed the political impact of new disclosures on this front would be negligible. People assumed stars behaved badly. But that wouldn’t make living through the reports any more pleasant.

On that front, Schwarzenegger suddenly had an opportunity. In November 2002, Joe Weider, the bodybuilding promoter who had brought Schwarzenegger to America, had sold his empire of fitness and bodybuilding magazines and nutritional supplement brands. The buyer was Ameri- can Media Inc., publisher of the National Enquirer and other supermarket tabloids.

Part of the value of the bodybuilding magazines was Weider’s close relationship with Schwarzenegger. The star still had a column, Ask Arnold, published in Muscle & Fitness, and American Media CEO David Pecker sought a meeting with Schwarzenegger to make sure that association would continue. The second week of July, as it became clear the recall would qualify for the ballot, Pecker met Schwarzenegger at Oak Productions in Santa Monica and proposed that the star become executive editor of two muscle magazines: Muscle & Fitness and Flex. Schwarzenegger did not commit immediately to Pecker’s proposal. It was another option in the giant bake-off.

Both Pecker and Schwarzenegger later told interviewers that there was no discussion of how the tabloids might cover a gubernatorial campaign, if there was one. But it was obvious that making a deal with Schwarzenegger might be better if the tabloids went easy on the star. Which is what the tabloids would do.

Schwarzenegger’s political advisors knew nothing of the American Media talks. Schwarzenegger not only kept Gorton and the other consultants at a distance, he also sought political advice from experts outside his employ. He invited the GOP pollster Frank Luntz to brief him on the results of focus groups he had done for the pro-recall organization, Rescue California.

One afternoon, Schwarzenegger invited Pete Wilson to his home. Wilson believed Schwarzenegger had decided to back Riordan, and was surprised to learn a candidacy was still possible. The two men, joined by Maria Shriver, talked for nearly three hours.

“I’m not concerned about you winning; I’m concerned about you making a decision without knowing what you’re getting into,” Wilson said he told Schwarzenegger. “Do you want this job badly enough to work at it as hard as you’re going to have to work in order to do it right? Arnold, it is going to mean from early morning till late at night, day after day, month after month. It will change your life, your family’s life.”

And what do you want to do with it? “You don’t want to wear the office like a boutonniere,” Wilson said. The former governor said he did not want to hear an answer right away. He just wanted Schwarzenegger to think about such questions.

A governor can do many things, Wilson said. Much of his power is to stop bad things. Sometimes, a governor can convince a legislature to act, but that would be extremely difficult in this era. In 2001, lawmakers of both parties had drawn their own districts to protect both Democratic and Republican incumbents, virtually eliminating competitive legislative elections in the state. Legislators had little incentive to challenge the status quo. To make changes in California, Schwarzenegger would have to use ballot initiatives. That would mean a lot of campaigns.

Wilson mentioned a conversation he had with Richard Nixon 40 years earlier about a variety of career options Wilson then faced, including whether to run for a state assembly seat. Nixon’s advice had been direct: You better do it because if you don’t, you’ll always question yourself about it.

Schwarzenegger thanked Wilson, and the former governor went home. His wife, Gayle, greeted him. How did it go?

“I don’t know,” Wilson said. “I’m afraid I talked him out of it.”

On Friday, August 1, Schwarzenegger called friends and supporters with the final word. He was out. Paul Folino, an Orange County tech executive, got the call on his cell phone. “I want you to know I’d like to do it, but I just can’t find a way there,” Schwarzenegger said. “It’s too much for my family.”

But there was a back-and-forth quality to these conversations. Jim Lorimer, his friend and business partner in the Arnold Expo, a massive fitness and sports convention in Ohio, advised Schwarzenegger not to run; California was not governable, Lorimer argued. But later that day Lorimer faxed his friend a memo with ten reasons why he should go for it anyway. Lorimer concluded his memo with verse by the nineteenth- century poet John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem about an unconsummated love between a judge and a maid.

For all sad words of tongue or pen, The saddest are these: “It might have been!”

On Sunday afternoon, August 3, the Schwarzenegger family drove out to a beach house that Riordan owned in Malibu. The star seemed resigned to his decision. But Riordan’s heart was still not in the race. Raising money in such a short time would be hard, he said.

“I said, ‘Dick, you’ve got to make up your mind, because if you don’t make up your mind and miss the [candidate filing] deadline [of August 9], then we are both screwed and the Republican party is screwed,’” recalled Schwarzenegger. “So, he said again, ‘OK, I run.’ But then we’re walking out of the beach house, and he said to me again, ‘I tell you one thing, though, you should run, Arnold.’”

I tell you one thing, though, you should run, Arnold.

The conversation reopened the door for Schwarzenegger. He felt a need for a departure, a new challenge. He had everything he wanted. He could smoke a cigar, sit in his Jacuzzi, put his kids to bed, and make more movies. It all felt a bit too comfortable.

By this time, the only debate that still mattered was taking place inside Schwarzenegger’s house in Brentwood. Schwarzenegger said that when he first told his wife weeks earlier, as they sat in the Jacuzzi, that he was interested in running, she started to shake. She would later say she worried about the effect on their lives, their careers, their family. But Schwarzenegger had two crucial allies urging him to run: his wife’s parents.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver had been her son-inlaw’s biggest booster. “He’s gonna run. Let him go,” Eunice Shriver told her daughter. Sargent Shriver loved the idea. “You’re making me very happy,” Sargent Shriver wrote in a July 11 letter to Schwarzenegger. “I can’t think of any person today that I would rather have in office. If I were a resident of California, I hope you realize that I’d be voting Republican for the first time ever!” Schwarzenegger had put his wife in a difficult position. If he didn’t run, much of the world would think she had blocked him.

Schwarzenegger said that he would not run without her blessing. “I don’t want to do this if you and the kids don’t feel it’s OK,” Schwarzenegger recalled saying. The two went back and forth until the final day. Schwarzenegger went to bed on the night of August 5, believing he would tell Jay Leno the next day that he was not making the race. Schwarzenegger and Shriver, on the morning of Aug.6, went over the decision one more time. “She knew I was going to say I’m not going to run,” Schwarzenegger recalled. “She said to me that morning, ‘Look, I just want you to know, if this really means a lot to you, you should do it.’”

Shriver picked up a page full of talking points for an announcement that he had withdrawn from the race. “This is me,” she said, according to her husband. She pointed to the list of reasons to run for governor. “This is you. You can’t be me, she added, and I totally support you in being you.”

He had his wife’s permission. But Schwarzenegger was still not certain.

Don Sipple, the political media consultant who had worked on Schwarzenegger's Proposition 49 campaign for after-school programs, answered his phone at 11 a.m. Wednesday. It was Schwarzenegger’s executive assistant, Kris Lannin Liang. If you have thoughts about what he should say if he decides to go for it, fax them to the house, Liang instructed. And don’t tell anyone.

Sipple took out a June 28 memo he had sent Schwarzenegger to outline messages for a candidacy, and reworked it. He looked back at the polling. He wrote that the people are “working hard, paying taxes, raising our families” while politicians were “fiddling, fumbling, and failing.” He sent the fax alongwith his cell phone number. No one called back.

Schwarzenegger sorted through Sipple’s fax and others as he got dressed. He received dozens of phone messages, but he didn’t return them. “Everyone wanted to call whoever they were obligated to in the journalistic world and be the guy who breaks the news. I was not going to fall for any of that,” said Schwarzenegger. “And I didn’t know myself. I didn’t want anyone to know. And to do that, you can’t tell anyone the final decision. Not Maria, either.”

Through lunch and the early afternoon, Schwarzenegger still couldn’t decide. “I tried to play it out and I couldn’t,” he said. So, with less than two hours before the taping, he resolved to let the moment seize him. “Finally, I said to myself, ‘Well, something will come out on ‘The Tonight Show.’ Just let it come out naturally when you’re on the show. It will be judgment time.’”

THE TONIGHT SHOW’ appeared on NBC at 11:30 at night, but the show was taped shortly after 4 p.m. in Burbank. Schwarzenegger arrived at the complex in a navy suit and white dress shirt, with no tie. In the green room, Leno and Schwarzenegger improvised a series of jokes about the star deciding not to run.

“It would have been funny if Arianna and I had debated,” Schwarzenegger said of the Greekborn Arianna Huffington. “No one would have understood anything we were saying.” Leno left to do his monologue. In the green room, Gorton confessed his disappointment in the decision not to run. Schwarzenegger gave no indication he had changed his mind. “Inside, I was thinking, ‘Beats me,’” he said.

On stage, Leno went right to the decision: “Let me ask you about this now. I know it’s been weeks and people going back and forth, and it’s taken you a while and you said you would come here tonight and tell us your decision. So, what is your decision?”

“Well, Jay, after thinking about this for a long time, my decision is . . .”

The loud bleep of a censor obscured the answer. It was a planned prank. The crowd laughed.Leno tried again.

“We’ve joked about this and thank you. It’s been in my monologue. It’s been a slow work week. It’s been good for like a thousand jokes. But seriously, what are you going to do? You said you were going to come here tonight and tell us. What are you going to do?”

“My decision obviously is a very difficult decision to make. It was the most difficult decision to make in my entire life except the one in 1978 when I decided to get a bikini wax.” During the laughter, Schwarzenegger breathed deeply. In that moment, he knew his decision was final. What flashed through his mind were the doubts he had heard expressed by so many people about whether he was capable of being a governor and about whether California was governable at all. The impossibility of fixing the state’s problems was what truly appealed; he was the guy who turned his boat towards the torpedo.

“Whenever people said it can’t be done, that was actually the thing that motivated me most,” he would recall in describe his thinking.

Wouldn’t it be fun to prove them wrong? Schwarzenegger faced Leno. “No, but I’ve decided that California is in a very disastrous situation right now,” he began, adding language from the Sipple memo: “The people are doing their job. The people are working hard. The people are paying their taxes, the people are raising the families, but the politicians are not doing their job. The politicians are fiddling and fumbling and failing!”

“And the man that is failing the people more than anyone is Gray Davis. He’s failing them terribly and this is why he needs to be recalled and this is why I am going to run for governor of the state. . .”

The roar of the studio audience swallowed the rest of the sentence. Leno did a double-take. This bit had not been rehearsed.

“What changed your mind?” Leno asked. “Did you change your mind?” Schwarzenegger described his family debate. He spoke as a certain victor—“then there will be the move to Sacramento.” But mostly he embraced the democratic message of the recall.

“That message is not just a message for California. That is a message that is from California all the way to the East Coast, for Republicans and Democrats alike to say to them: ‘Do your job for the people and do it well or otherwise you are hasta la vista, baby!’

Leno tried to set up him up for the Arianna Huffington joke, but he wouldn’t bite. “She is a very bright woman,” Schwarzenegger said.

A reporter asked George Gorton what would happen next. “I haven’t a clue,” he said. “I have to go make a plan.” He couldn’t make an outgoing call on his cell phone. Too many calls were coming in. He jumped in his car, still holding the press release announcing Schwarzenegger would not run for governor, and drove to the star’s home in Brentwood.

The top Republican in the state senate, Jim Brulte, congratulated Schwarzenegger by saying: “I see you’ve mastered the first rule of politics.” What is that?

“Never tell your staff anything.”

This was a lesson that Schwarzenegger may have learned too well. Yes, he was in charge, but of what? There was no campaign infrastructure because he hadn’t given anyone a heads-up there was going to be a campaign.

The first night, consultants and friends gathered at Schwarzenegger’s home. Many ideas were floated, some of them silly (one consultant wanted to change the way the candidate said “California”). Fewfew decisions were made. Schwarzenegger, wearing shorts, hung out at the pool and smoked cigars and listened much more than he talked. A campaign meeting, which took place the next day at the restaurant Schatzi’s on Main, wasn’t much better.

The Schwarzenegger campaign had no phone banks, no computers, no cell phones, no Blackberrys, and no campaign Web site. In the 12 hours after the announcement Wednesday afternoon, the star’s entertainment Web site, Schwarzenegger.com, had 70 million hits. It crashed.

In a normal election cycle, such start-up difficulties would not have mattered. There would be months before a primary election to get everything up and running. But the recall election was scheduled for October 7, just 60 days away. A campaign had started for which there had been no prep. There were no position papers on issues. There was no “vulnerability study,” political speak for the research that politicians routinely run on themselves to figure out how they might be attacked.

By Friday morning, the chaos caused by Schwarzenegger’s announcement caught up with him. The consultants booked the star on all three network morning shows, which began broadcasting at 7 a.m. eastern time—4 a.m. on the West Coast. Schwarzenegger had to rise at 3 a.m. after less than four hours sleep. For nearly any other candidate for governor at any other time and place, being able to appear on three TV networks in a single morning would be a huge coup. For Schwarzenegger, it was a strategic mistake. He could attract international attention anytime he wanted. There was no reason for him to lose sleep in order to appear on television.

Schwarzenegger did his first interview just after 4 a.m. Pacific time on NBC’s “The Today Show.” After Schwarzenegger answered two questions about how he had made his decision, host Matt Lauer pressed him on exactly how he would bring back the California economy. That led to a nonsensical exchange between the two men and, eventually, an abrupt end to the interview:

“Are you going to make your tax returns for the past several years available to the press?” Lauer asked.

Schwarzenegger fiddled with his ear piece. “Say again?”

“Are you going to make your tax returns for the past several years available to the press?” “I didn’t hear you.”

“Apparently we are losing audio with Arnold Schwarzenegger in Los Angeles,” Lauer said, sarcastically. NBC said it could find no technical problem with its audio equipment.

Bonnie Reiss, the former entertainment lawyer who had run Schwarzenegger’s Inner City Games Foundation, spent Thursday and Friday canvassing the consultants and trying to put a stop to the chaos. She sat in front of the fireplace at Schatzi’s and asked aides: What do we do to fix this?

One answer: a bigger team was needed. Schwarzenegger had to avoid specific issues while a campaign was built. After the TV appearances on Friday, Shriver joined a meeting of the campaign consultants, along with Reiss and the star’s investment manager, Paul Wachter. Shriver, Reiss, and Wachter all knew how to play bad cop to Schwarzenegger’s kindergarten cop. The presence of all three was a sign that changes were coming.

Shriver began by saying that she had met leaders all over the world, and that her husband could hold his own with any of them. She listed fifteen adjectives that described him, among them “courageous” and “intellectual.” The campaign needed to convey that sense of Schwarzenegger, and the best way to do that was to let her husband be himself.

Shriver did not raise her voice. Her preferred method was to fire questions rapidly, creating a Socratic shooting range that staffers would call the “full Maria.” Her target in this meeting was the consultants, specifically George Gorton. What is your plan? Where is the staff? What is your message? What was the point of these TV appearances? What direction is the campaign going in?

Gorton responded by explaining his approach to politics. He said he couldn’t answer many of Shriver’s questions without up-to-date polls and focus groups. The campaign should wait until it had new research before putting together the plan. He hadn’t had any polls in the field because Schwarzenegger’s candidacy had been a surprise.

Shriver pushed back, saying she didn’t believe in polls and asking why there wasn’t a clearly defined slogan for the campaign. She suggested that Schwarzenegger would want to be known as “The People’s Governor.” Gorton replied that he would have to poll on that—an answer that may have proved to be the last straw.

She suggested that Schwarzenegger would want to be known as “The People’s Governor. ”

Bob White had taken Friday off. When he turned his cell phone back on late in the afternoon, he was deluged with messages from the Schwarzenegger camp, one of the last from Shriver, who urged him to return her call first. White had run Pete Wilson’s campaigns but thought he had gotten out of the business for good. He was an institution in Sacramento, where he made his living offering strategic advice to companies but did not, at least according to California’s hard-to-understand laws, lobby the government. Newspapers would point out that for someone running against special interests, Schwarzenegger’s hiring White as campaign manager did not fit the script. But by late Friday night, Schwarzenegger had convinced White to take over.

During a meeting that first Saturday morning at Oak Productions, Governor Wilson walked in unexpectedly, carrying a list of suggestions for policies Schwarzenegger might adopt. White quickly realized the freewheeling campaign needed order and routine. He called Pat Clarey, a deputy chief of staff to Wilson, who was now an executive of HealthNet Inc. She, in turn, reached Marty Wilson, another old Wilson hand (no relation to the former governor) as he drank a martini on a train from San Francisco to Sacramento.

By Saturday night, Clarey, Marty Wilson, and White were meeting in Brentwood with the Schwarzeneggers. When Shriver asked questions about strategy, Wilson explained that he and Clarey were operations people. Clarey would run the campaign day to day. Wilson would coordinate the fundraising, coalition building, and the campaign budget. Clarey and Wilson would retain some version of those roles—Clarey as the inside chief, Wilson as the operational captain of the team of outside consultants—well into Schwarzenegger’s governorship.

Clarey and Wilson oversaw the process of turning offices in Schwarzenegger’s Santa Monica building into a headquarters. Clarey assembled a campaign staff, calling the employers of some recruits to request twomonth leaves. White instituted staff meetings at 8 a.m. and 6 p.m.

White made the campaign more businesslike and happier. But he never gained control, in part because Schwarzenegger was in control, and encouraged internal competition. He liked to have advisors competing to give him the best ideas. Schwarzenegger’s style might sometimes sow confusion, but it meant that when decisions got made, he was the one who made them.

In shielding his campaign’s start-up difficulties from the public, Schwarzenegger had 134 unwitting allies—the other declared candidates for governor. To qualify for the ballot in the recall election, all one needed was $3,500 and the signatures of sixty-five registered voters. With the recall receiving news coverage worldwide, running for governor had become a marketing opportunity. At the polls, one’s name on the ballot might be seen by 10 million people.

But this candidate circus only deflected so much. Schwarzenegger was deluged by questions about his plans and policy intentions from a planet’s worth of media, politicians, and interest groups. He didn’t have answers to all those questions, so he spent much of his time in public talking about the after-school programs he’d built and the ballot initiative he’d passed the previous year to guarantee after-school funding in California.

Prop 49, as the initiative was known, might have been his only credential in California governance, but it was a considerable one. The previous November, as Davis was barely crawling to re-election, Schwarzenegger had run a model campaign for a ballot initiative on a serious policy issue.

That issue was after-school programs, a subject he knew intimately. Over the past decade, he’d be meticulously built up a network of afterschool programs in cities around the country. But Schwarzenegger, in organizing Prop 49, had relied on more than his own work. He’d consulted widely with experts and interests to fashion a carefully drawn measure—there were more than 20 drafts—to fund after-school programs in California at a higher level than in any other state in the U.S. With no powerful interest group championing after-school programs, he’d built a broad and bipartisan coalition that included traditional enemies, like teachers’ unions and taxpayer groups.

The campaign gave him a victory—with 56 percent of the vote—and his bumper sticker slogan for his political career: “Join Arnold.”

Now, in the early days of his surprise gubernatorial campaign, after-school programs were all that Schwarzenegger was prepared to talk about. In his first week on the trail, the candidate even flew to the East Coast for two days to attend a long-scheduled event at his After-School All-Stars charity. Before hitting New York, he stopped in Hyannisport and huddled with his Democratic in-laws. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., agreed to help with the environmental platform. In Harlem, 33 camera crews trailed him. He took no questions. New York media left unimpressed.

“He couldn’t last one round with Hugh Carey!” columnist Jimmy Breslin bellowed, referencing an ex-New York governor. Money was a much larger concern than an agitated press corps. Schwarzenegger’s New York trip included a lunch at the Four Seasons with prominent Republican political donors. No money changed hands, and the Schwarzenegger campaign at first denied that the lunch had taken place. Schwarzenegger would fund much of the campaign’s cost himself. But it was not in Schwarzenegger’s best interests to turn down funds. By accepting donations, he would guarantee that less money would be available to his rivals.

Schwarzenegger did, however, want to avoid taking money from people or groups who might negotiate with him as governor. A fundraising policy approved by the candidate on August 21 laid out rules. As governor, Schwarzenegger would not use his appointees to solicit campaign funds. He pledged not to take money from political action committees, trade associations that represented only one industry, public employee unions, or “individuals, companies, or corporations that are engaged in gambling or tobacco.”

That notably excluded money from the state’s Indian tribes, which had a monopoly on casino gambing in the state. That decision to stay away from tribal money did not get much attention at the time, but it would become an essential strategy late in the campaign.

Schwarzenegger’s statement at “The Tonight Show” studio that he needed no money deterred some donors. The candidate also was reluctant to make phone calls to potential donors. He dislikeed asking for money and hated the sense that he might owe someone as a result. Marty Wilson had to delay the campaign’s first payroll for five days.

To make fund-raising easier for Schwarzenegger, Wilson conducted conference calls, with Schwarzenegger on one line and Wilson on another. Schwarzenegger would talk about the campaign and his goals for the state. Then Wilson would ask for money. Wilson tried to be in a different room during the calls so he wouldn’t have to see the candidate’s pained face.

Much of the money given to Schwarzenegger’s campaign went to the purchase of TV time. Sipple filmed the first TV ad on Friday, August 15, nine days after Schwarzenegger joined the race. The set was Schwarzenegger’s old compound of homes in Pacific Palisades. The opening scene showed the candidate walking outside and then talking in an office.

“I am running for governor to lead a movement for change and give California back its future,” he said, as the camera pushed in tight until his face filled the whole screen and his eyes stared directly at the viewer. “I want to be The People’s Governor. I will work honestly, without fear or favor, to do what is right for all Californians.”

With the media starved for any new footage of Schwarzenegger, the advertisement was shown on TV news and entertainment programs more often than it appeared in purchased 60-second spots. It was one of many advantages that his celebrity provided.

Another was his ability to attract high-profile campaign advisors. On August 13, he announced the billionaire Warren Buffett as cochair of his campaign’s economic team. The choice of Buffett, a Democrat, drew rebukes from Republicans. Two days later, the rebukes became screams when, in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Buffett criticized Proposition 13, the 1978 tax-cutting initiative, led by the late anti-tax activist Howard Jarvis.

Even worse, Buffett also had criticized the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, which had been preparing to endorse Schwarzenegger, but quickly backed away. “It was a disaster,” Gorton recalled. “We needed that anchor on the right. I thought the campaign was in danger of coming apart then.” Gorton and the former Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association president Joel Fox spent two weeks trying to win back the Howard Jarvis endorsement. Schwarzenegger finally clinched the “re-endorsement” after meeting with Jarvis’s widow, Estelle.

But Schwarzenegger was stagnant in the polls. One newspaper poll showed Lt. Gov Cruz Bustamante, who had jumped into the race against the advice of Davis and other Democratic allies, with a lead of 25 percent to Schwarzenegger’s 22 percent.

The campaign’s own first poll painted an only slightly brighter picture. In that survey, the recall looked strong. Fifty-eight percent of Californians would vote to remove Davis. And the poll showed Schwarzenegger to be personally popular, with 62 percent of Californians having a favorable opinion. But Schwarzenegger had only 28 percent of the vote in this internal survey, the same as Bustamante. who had jumped into the race against the advice of Davis and other Democratic allies, with a lead of 25 percent to Schwarzenegger’s 22 percent.

The campaign’s own first poll painted an only slightly brighter picture. In that survey, the recall looked strong. Fifty-eight percent of Californians would vote to remove Davis. And the poll showed Schwarzenegger to be personally popular, with 62 percent of Californians having a favorable opinion. But Schwarzenegger had only 28 percent of the vote in this internal survey, the same as Bustamante. The star’s challenge was clear: many of the people who liked him didn’t plan to vote for him.

Seventy-two percent of voters who believed Schwarzenegger would make a bad governor cited his lack of experience as a reason for not supporting him. But the poll also showed the way Schwarzenegger could change those impressions. Once people learned about Prop 49, it became an invaluable political credential. For those who liked Schwarzenegger, the most common reason was his “record of supporting kids.”

Just days after entering the race, Schwarzenegger reached former U.S. Secretary of State and Secretary of the Treasury George Shultz at his office at the Hoover Institution on the Stanford campus. Shultz started the conversation by giving the candidate thirty seconds to explain why he should back him. Schwarzenegger said he wouldn’t spend more money than the state had. It was the right answer for Shultz.

Two days after Schwarzenegger’s conversation with Shultz, the candidate called his colleague John Cogan, a budget advisor to President George W. Bush and other conservatives, and invited him to his home in Brentwood. Joined by Pete Wilson’s former finance director Russ Gould, Cogan and the candidate met on Saturday, August 16. As they drank lemonade, Cogan and Gould lectured on the state of the budget. Schwarzenegger asked questions.

The session went so well that Schwarzenegger asked Joe Rodota, the campaign policy director, to put together similar study hours on other issues. These classes would be called Oak Institute by some aides, Schwarzenegger University by others.

They would do more than inform the candidate. They would contribute to the reshaping of the policy direction of the state.

Schwarzenegger’s only instruction to Rodota about Schwarzenegger University was that he wanted the best briefers in the world. He did not care whether his instructors were Democrats or Republicans, or even whether his instructors intended to vote for him.

The candidate resisted both external and internal pressure to cut these briefings short so he could attend to other campaign needs. For most of August, Schwarzenegger faced daily criticism from reporters, including me, for failing to describe his platform or answer questions from journalists. The campaign’s communications staff pressed internally for more public events. And finance staffers wanted more fund-raisers scheduled. Schwarzenegger argued that he needed to know the issues first. Schwarzenegger University would remain in session for another two weeks.

Schwarzenegger University included a course in the “Powers of the Governor,” laid out initially in a nine-page memo that had been produced by Rodota.

“The office of the governor of California is second only to the presidency of the United States in scope and authority,” the memo began. The only two elected officials in the United States with greater authority to make appointments were the president and th e mayor of Chicago, the memo emphasized. Schwarzenegger learned from the memo how to veto a bill, how to submit government reorganization plans, how to call a special session of a legislature, and how to call a special election. These last two powers would prove to be Schwarzenegger favorites.

Most of the Schwarzenegger University briefings were oral. The university’s lone student kept the tone light and personal. In an early briefing on gun control, Schwarzenegger was asked if he owned any guns. “As a matter of fact, I own a tank,” he said—he had found the tank he drove in the Austrian military and shipped it to Ohio, where it sat in a military museum.

After Schwarzenegger seemed bored by his first briefings on education, Rodota convinced Bill Lucia, a dynamic Californian who worked at the U.S. Department of Education, to do an additional education session. Lucia, instructed to be as energetic as possible, jumped out of his chair. Schwarzenegger tried, in vain, to hire him.

Harvard professor George Borjas, an expert in the economics of labor, flew out from the East Coast to lead “a very academic presentation” on immigration. “He didn’t need my help,” said Borjas. “From his own experience and the experience of his friends, he knew more about the subject than any politician I ever met.”

Aides often found the sessions long and grueling. But Schwarzenegger University’s only enrolled student “loved every second of it,” he would recall. “I knew the entertainment world. I knew the business world, but I had never really spent that much time, with quality people like hospitals directors, prison wardens, the advocates for Mexican American rights—all the people who thought about California and poured out their concerns and ideas… I really got an education.”

Nevertheless, the candidate kept his Schwarzenegger University studies secret. Expecting to be governor, Schwarzenegger wanted detailed plans. But as a candidate, Schwarzenegger and his strategists believed the public wanted to vote for an outsider who could sweep Sacramento clean, not a man with a fivepoint plan. Schwarzenegger offered one brief, but crucial, early glimpse behind his policy curtain. On August 20, he convened a meeting of his “economic recovery team” at an airport hotel in Los Angeles. Working with Rodota and his investment advisor Paul Wachter, Schwarzenegger had recruited two dozen people, including Oracle president Ray Lane and David Murdock, the billionaire owner of Dole Food Co.

Photographers and reporters were allowed to view only Schwarzenegger’s welcome to the team. Once journalists had left, Warren Buffett took over the early discussion. He said California had lost so much credibility with the markets that the state, the fifth-largest economy in the world, was having trouble selling its bonds. California would have to pay off $14 billion in short-term debt in June 2004, and had no plan to avoid default. Without a plan, the state might require a federal bailout by the following summer.

The group then reviewed the approach to the deficit that Cogan had first outlined for Schwarzenegger. The only person to challenge this strategy of borrowing and slowing spending growth was UCLA economist Ed Leamer, who had met privately with the candidate in one of the Schwarzenegger University sessions a few days earlier. Leamer believed that the economy could turn soft again and foil the strategy. The only way out of the budget trouble was a temporary tax increase, he said.

Leamer was heavily criticized by former U.S. Treasury Secretary George Shultz in the meeting, but he would prove prophetic. After the Great Recession, first Schwarzenegger and then his successor, Gov. Jerry Brown, would be forced to back temporary tax increases to stabilize California’s volatile budget.

Outside the meeting, more than 160 members of the international media waited in a hotel ballroom for the first official press conference of the Schwarzenegger campaign.

The candidate started with a brief statement about California’s budget troubles. He promised a 60-day, line-by-line audit of the budget, but claimed he had no specific plan for the budget. Schwarzenegger opened it up to questions.

Would he ever consider raising taxes? Asked one reporter.

The candidate had planned his own response. He said, as quickly and quietly as he could, that an earthquake, natural disaster, terrorist attack, or some unforeseen circumstance could require a tax increase. Then, having left the door carefully ajar, he delivered a sound bite that would be irresistible to TV directors and would make him sound like an implacable foe of tax increases.

“The people of California have been punished enough. From the time they get up in the morning and flush the toilet, they’re taxed. Then they go and get a coffee, they’re taxed. They get into their car. They’re taxed. They go to the gas station. They’re taxed.”

The rhythm built from there. “They go to lunch. They’re taxed. This goes on all day long. Tax tax tax tax tax.”“Even when they go to bed, you can go to bed in fear that you may get taxed while you’re sleeping. There’s a sleeping tax.”

A reporter asked whether Buffett’s comments that California property taxes were out of whack “made sense.”

Schwarzenegger smiled. “First of all, I told Warren if he mentions Prop 13, he has to do five hundred sit-ups.”

Even reporters laughed. With one quip, the candidate had distanced himself from his famous advisor. But he had done it without insulting Buffett. Schwarzenegger, with a touch of humor, could put even a billionaire in his place. The clip would be replayed so often that California voters in surveys came to associate Prop 13 more closely with Schwarzenegger than any other politician. With one joke, Schwarzenegger had turned a liability into a strength.

A survey from a Republican who considered a recall campaign, Bill Simon Jr., found the power of Schwarzenegger’s personality. The poll presented voters with a nameless candidate who shared Schwarzenegger’s qualifications and policy views. The poll “showed us that there was no way they would vote for somebody that held all of these positions that Arnold held,” said Wayne Johnson, Simon’s strategist. But when the pollsters said these were Schwarzenegger’s positions, those surveyed said they would vote for him anyway.

Two days after his press conference with Buffett and Shultz, Schwarzenegger campaigned in public in California for the first time. The day’s schedule called for him to have lunch with businessmen on the open-air patio of a restaurant on Main Street in Huntington Beach a city in Orange County. From there, he would stop in various shops on a two-block walk to the pier.

He would never get that far. By 11 a.m., thousands of people descended on Huntington Beach, seeking a glimpse of the candidate. Police closed down streets to control the size of the mob. It was too late. Old men in electric wheelchairs, surfers, parents with babies, women in bikini tops, and young men in black “Terminator for Governor” T-shirts all pressed as close as they could to Schwarzenegger.

The candidate was jostled after he walked out of a surf shop on Main Street. A reporter assigned to follow him was knocked to the ground. I was among those reporters who was pushed and shoved. When Schwarzenegger waded into a group of media people to give a brief statement, he had to use a bullhorn to be heard. Rob Stutzman, one of the campaign’s communications directors, was reduced to using his body to prevent the crowd from surrounding the candidate’s SUV.

“Please stand back,” Stutzman begged. “Don’t get run over.”

As soon as Schwarzenegger was gone, Stutzman and other aides held an emergency meeting on the sidewalk. Many of these advance men and communications experts had spent their careers trying to build crowds for politicians. Schwarzenegger posed a new problem. How could the rabid crowds be managed so no one got hurt?

The campaign responded by keeping the candidate’s schedule a secret until mere minutes before future events. Pat Clarey, who would become his first chief of staff, convinced Republican politicians around the country to loan aides for crowd control. Finally, Clarey arranged to rent hundreds of metal bicycle racks to serve as barriers between Schwarzenegger and the public.

Schwarzenegger also secretly recruited Mike Murphy, a strategist who had worked for GOP candidates in blue states, as the campaign’s top strategist. Murphy said yes, for reasons that went beyond the immediate campaign. Murphy was a talented photographer and writer who wanted to make films, and he believed a highprofile California campaign would provide a platform to enter the entertainment business.

In the campaign, Murphy would have no specific title. Schwarzenegger assigned people areas of responsibility, not titles. Murphy would not do a bloodletting, but he brought in two young policy aides, as well as Florida Governor Jeb Bush’s spokesman Todd Harris to join the communications operation. At first, Murphy was stunned by the free-flowing nature of Schwarzenegger’s operation. But Schwarzenegger put him at ease.

Don’t be intimidated, the star warned. “I like directors who tell me what’s not working. Just look me right in the eye and tell me.”

The last week of August, Murphy found a spot on the second floor of Schwarzenegger’s Santa Monica office complex. He kicked the campaign’s Internet team out of their large office at the end of a hall and built a war room there. A huge new calendar on the wall listed Schwarzenegger’s public events, a theme for the day, and a schedule of TV ads. To Murphy, setting up this infrastructure was Campaign 101. It was a measure of the chaos in the campaign that no one had done this before.

The Schwarzenegger University sessions had produced a much better-informed candidate, with details and surprising plans, but few Schwarzenegger policies had been committed to paper. Murphy assigned Trent Wisecup and Rob Gluck, the two aides he’d brought with him, to write up everything over the Labor Day weekend. When Murphy walked into the war room Tuesday morning to check on the exhausted aides, he bellowed, “I love the smell of policy in the morning!”

The exercise produced a white binder, the Join Arnold Policy Binder, that Schwarzenegger carried as he campaigned. By campaign’s end, it had twenty-three pages on “Putting California’s Fiscal House in Order,” seven on “Fixing the Runaway Workers’ Compensation System,” twelve pages on “Meeting the Needs of California Students,” and four on “The People’s Reform Plan.”

In most campaigns, these documents would be called position papers. But Schwarzenegger objected that he did not hold positions, he took actions. So the policy documents began, “As governor, I will. . . . ” The candidate himself reviewed the new policy documents to check for active verbs.

At Schwarzenegger’s insistence, his aides gave the policy binder an unusual appendix that recorded every promise he made. The list eventually ran to six single-spaced pages. Schwarzenegger took these promises seriously; he would pursue virtually every idea in the policy binder he kept during those meetings.

To take one example. David Crane, a Democrat and friend of Schwarzenegger’s since the 1970s, came down from San Francisco, where he was partner in a financial services firm, to lead sessions on energy and on workers compensation. Workers’ compensation reform would be his first major legislative victory as governor. Schwarzenegger would follow that up with major advances in solar infrastructure.

Just before Labor Day, the campaign hired Republican pollster John McLaughlin to conduct a new “benchmark” poll. The poll asked voters their views not only of Schwarzenegger, but of other gubernatorial candidates, of Governor Davis, of the condition of the state, and of a dozen different issues.

McLaughlin had experience overseas working for, among others, the Likud Party’s Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel. The multicandidate, multiparty races in those parliamentary democracies were more like the recall than most American campaigns, and they had taught McLaughlin a crucial lesson. When there were more than two candidates, the center was the last place you wanted to be. Such elections were won by building a devoted base on one side or the other.

Completed on September 7, McLaughlin’s benchmark poll showed the recall would pass with 54 percent of the vote. But Schwarzenegger and Bustamante were in a dead heat to succeed Davis, with about 25 percent each. McLaughlin, who lived in New York, caught a plane from Newark to Los Angeles to deliver these results in person to Murphy, Sipple, and the rest of the campaign team.

McLaughlin had pointed advice for the strategists. The recall was far more popular than any of the candidates to replace Davis. For Schwarzenegger to gain, he had to become the recall in voter’s minds.

Who were the recall supporters? McLaughlin’s benchmark survey showed they were against raising taxes. They were ferocious in their disdain for Davis’s decision to triple the state’s vehicle license fee. And they believed the state was controlled by interest groups.

These voters included Democrats and independents, but the balance was conservative Republicans. Schwarzenegger could build a base on the right without alienating other recall supporters by focusing his campaign on issues— taxes, workers’ comp, the power of Indian gambling interests—on which recall supporters of all stripes agreed. An internal campaign memo, headlined “The Winning Candidate for Conservatives,” outlined the strategy. “While AS will have broad appeal, he must nonetheless forge a base of support within the California GOP...If AS can give them the tax issue, it can go a long way toward seeing conservatives give great credence to the ‘winability’ factor.”

To create this GOP base, Schwarzenegger needed to give his candidacy a more Republican feel. The candidate scheduled daily appearances on local talk radio shows hosted by conservatives—the more the better, Schwarzenegger told his team. The hosts seemed thrilled to have a chance to talk with the star. There were as many questions about movies and bodybuilding as politics.

Even those who challenged Schwarzenegger’s views still praised him, especially the Fox News Channel’s Sean Hannity, who forced Schwarzenegger to recite his views on social issues on his nationally syndicated radio show.

Hannity: Do you consider yourself, for example, prolife or prochoice?

Schwarzenegger: Pro-choice. Hannity: Do you support partial-birth abortion?

Schwarzenegger:I do not support partial-birth abortion.

Hannity: Are you in favor of parental notification?

Schwarzenegger: I am, but in some cases where there is abuse in the family or problems in the family, then of course not.

Hannity: Do you support the Brady bill or the assault weapons ban or both?

Schwarzenegger: Yes, I do support that and also I would like to close the loophole on the gun shows.

Hannity: Do you support gay marriage?

Schwarzenegger: I do support domestic partnership.

Hannity: But not gay marriage?

Schwarzenegger: No, I think gay marriage is something that should be between a man and a woman.

That last line was an all-time classic malapropism, but it didn’t slow down Schwarzenegger. Before the show was over, he had come out against school vouchers, for the decriminalization of marijuana for medicinal purposes, and against offshore oil drilling. Hannity agreed with almost none of this, but praised Schwarzenegger for his honesty. Hannity would host a town hall for the candidate later in the campaign.

Bob White and Maria Shriver had recruited Landon Parvin as campaign speechwriter. Schwarzenegger believed that being funny was important. And Parvin, a former aide to Reagan, had made his reputation by authoring a humor column for the Congressional newspaper Roll Call and for secretly writing many of the selfdeprecating speeches given by presidents and politicians at Washington roasts. Parvin worked out of his house in Fredericksburg, Virginia. But he was ahead of schedule on a book and decided he needed to shake up his life. Parvin knew little about California politics and had not followed the recall closely.

When he wrote speeches for other politicians, Parvin would sit down with them and find out what they wanted to say. Schwarzenegger had neither the time nor the inclination to do that. He wanted his speeches to sound natural—the way he talked. So Parvin became a fly on the wall. He sat in on Schwarzenegger University sessions. He read transcripts of Schwarzenegger’s media interviews. He listened in on fundraising calls. He ate egg-white omelets for breakfast at the Firehouse restaurant, where the skinny speechwriter stood out among a clientele heavy in bodybuilders. On some nights, Parvin would go to Schwarzenegger’s home, listen to him talk to friends, and take verbatim notes to capture his vocabulary and cadence.

Eventually Parvin characterized Schwarzenegger as a variation on Reagan. The two had similar messages, but Schwarzenegger’s language was more staccato. Reagan had an air of reserve. Schwarzenegger craved a closer connection with the audience. And while most politicians tried self-effacement, Schwarzenegger preached the gospel of self-improvement.

Before starting a speech, Parvin received an outline from Murphy detailing the elements that had to be included—specific policy relevant to that speech. Once Parvin completed a draft, Murphy added one-liners that would make the newspapers and the TV broadcasts. Then Schwarzenegger read through the text with his dialogue coach and friend, Walter von Huene. A former acting coach on Happy Days and a TV director, von Huene had gotten to know Schwarzenegger while working with the child actors in the star’s 1996 Christmas comedy, Jingle All the Way. The two men had strong personal chemistry. Born in Germany, von Huene came to California in 1952 when he was just three years old; he learned German from his grandmother and parents. Von Huene worked with Schwarzenegger on Batman & Robin, The Sixth Day, and Terminator 3, going over Schwarzenegger’s lines one by one to improve the actor’s delivery.

“I come to you today not as the Terminator or the guy who fought the Predator. ”

Von Huene would perform a similar service in Schwarzenegger’s political life. Which words should he emphasize? When should he pause? If some phrases written by Parvin and Murphy did not work, von Huene and Schwarzenegger sent the speech back.

“I come to you today not as the Terminator or the guy who fought the Predator,” Schwarzenegger began his speech at the campaign’s first rally. Truth be told, he came to the rally, in front of a movie theater in Fresno on August 28, as a politician having a rough afternoon. On his way to the speech, he had toured a local factory while reporters pestered him about an interview he’d given to a skin magazine, Oui, in 1977. In the interview, Schwarzenegger described engaging in group sex at Gold’s Gym and receiving blow jobs backstage at Mr. Olympia contests.

Schwarzenegger said at the factory in Fresno that he didn’t remember the interview. He later suggested he had made up the stories in 1977 to sell bodybuilding. “I said a lot of things that were not true,” Schwarzenegger recalled. “It was only to dramatize situations—to dramatize things in order to make people . . . say, ‘I am interested to watch this guy. This is an interesting personality.’”

In saying that he had lied at the time to sell himself and bodybuilding, Schwarzenegger was almost certainly telling the truth. The campaign began to trot out this line against any provocative quote that emerged from Schwarzenegger’s past. This was an unusual approach for a political candidate: He lied—so what? But it reflected a core Schwarzenegger strategy for handling criticism—to avoid being defensive, to steer your boat towards the torpedo. In this case, it defused the issue. When Schwarzenegger arrived at the rally and saw the crowd of more than two thousand, his worries seemed to vanish. Some people had been waiting since lunchtime for the 5 p.m. speech. The candidate was driven up to the stage in a dark SUV. He exited to a tape of the 1980s metal band Twisted Sister singing “We’re Not Gonna Take It.”

Twisted Sister had named the 1985 album on which “We’re Not Gonna Take It” appeared after an early Schwarzenegger film, Stay Hungry. A few conservative taxpayer advocates thought the song was a nod to Howard Jarvis’s old cry: “We’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it anymore.” (That phrase itself had been made famous in the 1970s in the movie Network!)

The song matched perfectly the over-the-top feel of the recall campaign. California was hot and dry, its citizens angry and agitated. Schwarzenegger crowds wore light, loose-fitting clothes. The sixty-day race was about the length of a decent summer fling, the amount of time a huge hit movie stuck around in theaters.

Schwarzenegger talked for seven minutes. The crowd was so loud that, even speaking through a microphone, Schwarzenegger was difficult to hear. A dozen ROTC cadets chanted the candidate’s name. Schwarzenegger walked along the edge of the stage, signing Terminator action figures and old bodybuilding magazines.

The TV stations had cut away while Schwarzenegger shook hands and signed autographs. So, Murphy figured out a simple, ingenious way to keep the cameras on the candidate even when he wasn’t speaking. “I want a box of T-shirts wrapped up tight like footballs,” he told Fred Beteta, who advanced campaign events.

When he saw news coverage of his first throw, Schwarzenegger said, “Give me more T-shirts.” For the price of a couple dozen T-shirts, Schwarzenegger could get hundreds of thousands of dollars-worth of air time.

As the campaign progressed, Schwarzenegger made his own news by seeking endorsements from groups that typically did not give them to Republicans, or anyone at all. Many of his aides thought this was a waste of time, but the candidate insisted. Swinging for the fences, Schwarzenegger struck out at first. He called prominent Democrats, but a “Democrats for Arnold” coalition never took off. Schwarzenegger appeared to have pulled off a coup with an endorsement from the state firefighters association (public employees rarely backed Republicans), but a rival firefighters group aligned with Governor Davis attempted to replace the leaders of the association.

Schwarzenegger turned next to the state’s business community. Local chambers of commerce were opposing the recall; the Los Angeles Area Chamber, chaired by Maria Shriver’s personal attorney, opposed the removal of Davis. The California Chamber of Commerce, the statewide group, had a policy of not issuing endorsements in state races. The chamber nevertheless had invited Schwarzenegger to speak.

Jeff Randle, the consultant who headed the campaign’s political operation, saw the invitation and tried to use it to win an endorsement. “We’ll come and speak,” Randle told the chamber’s Cassandra Pye when she called. “Just give me an endorsement.” Pye laughed at first, but she mentioned the request to the chamber’s president Allan Zaremberg, who to her surprise did not dismiss it entirely. The chamber executive committee was reluctant at first. But that reticence vanished when Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante announced his budget plan, which included tax increases on businesses to close the budget deficit.

Schwarzenegger made a point of leaving the campaign office by six o’clock each evening to go for a workout. But with Randle begging, the candidate stuck around for an early evening phone call with the chairman of the chamber’s board, Raymond Holdsworth, a Los Angeles technology executive. Holdsworth said he would take the matter to his board at a meeting on Friday, September 5, at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Dana Point in south Orange County.

The board meeting offered genuine suspense. Forty reporters had gathered in a hotel courtyard. Randle felt ill. If the chamber chose not to endorse, the journalists were sure to call it a defeat.

Schwarzenegger gave a brief speech about the high cost of doing business. He told the story of his ten-year-old son Patrick’s business selling milk and cookies to construction crews remodeling homes in Brentwood. “I’m worried about him, because every day I’m prepared to come home and find his workers’ compensation is going to close him down,” Schwarzenegger joked. He took a few questions and left to wait for the verdict in a hotel room.

Schwarzenegger did not receive unanimous support. And chamber members said the decision did not change their policy of avoiding endorsements in statewide races. But the recall was a historic event. The endorsement was front-page news in many of the state’s papers.

As Schwarzenegger drove yet another Republican from the race, he began to look more like a candidate. He once favored leather jackets and short sleeves. By September he was sometimes wearing suits (48 regular), dress shirts (17/35), and solid-color ties.

Schwarzenegger started holding his own town halls, called “Ask Arnolds,” in each major media market. Ask Arnolds were not open to the general public. The campaign invited only members of supportive groups and local volunteers. The levels of the stage on which audience members sat were customized to the candidate’s height so that Schwarzenegger was looking up at his questioners—a more attractive pose than looking down. At the San Diego Ask Arnold, the invited guests enlivened the event by quarreling with one another over how close they could sit to Schwarzenegger.

Ask Arnolds were often scheduled during the day, followed by fundraisers at night. On an evening in September, Schwarzenegger had events at the home of venture capitalist John Hurley in San Francisco’s Russian Hill, and at the Blackhawk Automotive Museum across the bay in Danville.

The campaign press office had arranged for a TV reporter to ask Schwarzenegger a quick question on his way out. The candidate exited a side door and walked straight to the reporter, whose cameraman had the tape rolling. As the reporter asked his first question, Schwarzenegger stopped him.

“You know what? I didn’t like the look of the exit. I walked right to you. Boring. It should seem like I didn’t know, like you just grabbed me on the way out,” he said. Schwarzenegger went back inside the museum and exited the same side door, but this time he walked away from the camera. After a few steps, Schwarzenegger turned around and came over to take a few questions. The candidate, an actor directing himself in this raucous political story, had produced the picture he wanted.

“You know what? I didn’t like the look of the exit. I walked right to you. Boring. ”

Schwarzenegger, with just a few weeks to go,had only one rival remaining on his right: Tom McClintock.

The campaign’s polls suggested that McClintock was the only person standing between Schwarzenegger and the governorship. McClintock had little money. He had spent twenty years in the legislature, but did not hold leadership posts. But he was eloquent and familiar to the conservative talk radio listeners who fueled the recall. With other Republicans out of the race, McClintock was running a strong third, with support in the double digits. He had many of the state’s most conservative voters in his camp.

How to react to McClintock’s challenge was a matter of constant debate in the Schwarzenegger campaign. Shriver and Reiss, both Democrats, had long argued for a centrist campaign that would transform California politics and the Republican party in the process. The other consultants disagreed. It might be nice to change California politics. It would be nicer to win. The only sure way to do that was to pry conservative voters away from McClintock.

Jan van Lohuizen, a pollster who worked both for President Bush and California’s largest teachers’ union, produced a memo on September 12 arguing that Schwarzenegger badly needed McClintock’s conservative voters. Van Lohuizen’s surveys of Democrats suggested that no more than 20 percent of them would vote for Schwarzenegger. If Schwarzenegger didn’t continue to court conservatives, the Republican vote would be split. The result: Governor Bustamante.

Publicly, Schwarzenegger was full of praise for McClintock. Privately, he signed off on a strategy designed to push the state senator out of the race. Schwarzenegger’s conservative supporters asked McClintock backers to stop donating to his campaign. This was a war of attrition. McClintock raised $2.4 million in his campaign. Schwarzenegger would spend nearly ten times that.

In the battle for conservative votes, Schwarzenegger adopted much of McClintock’s economic platform as his own. At his campaign’s beginning, McClintock had identified five issues on which he, as governor, would draft ballot initiatives to allow voters to enact new laws directly. Schwarzenegger embraced all five issues—workers’ compensation, protection of local government funds, making lawsuits more difficult to file, the contracting out of some state government services, and a constitutional amendment to give the governor more power to cut spending.

On Friday, September 12, Schwarzenegger received a memo from his consultants about the California Republican Party Convention, which would take place that weekend at the LAX Marriott hotel. The party’s 1,400 delegates, the memo explained, were more conservative than party voters, and their conventions usually were of interest only to political junkies. This weekend, the memo concluded, you are going to change that.

The party was unlikely to officially endorse either candidate at the convention itself, but the weekend offered a chance to win the backing of Republican regulars and set the stage for the party’s endorsement in the weeks ahead. In this contest, Tom McClintock had left Schwarzenegger a huge opening. Knowing that the convention delegates were his natural ideological allies, the conservative state senator would give a speech, but not otherwise have much of a presence.

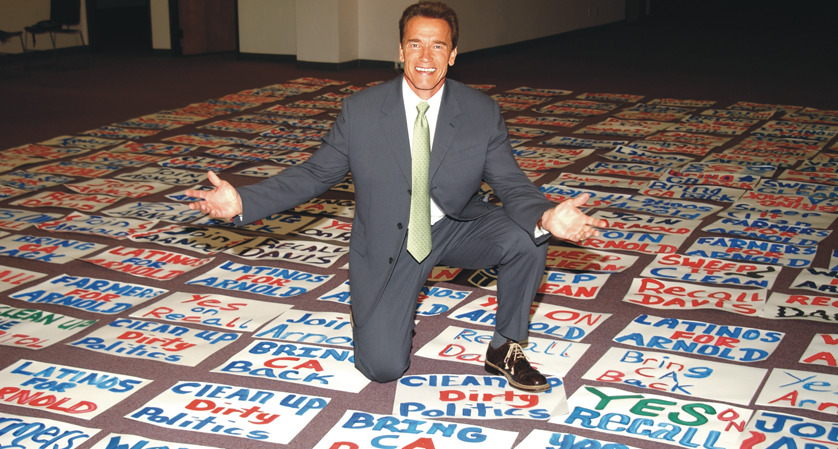

Jeff Randle had a plan to fill the vacuum and push the party to endorse Schwarzenegger. The strategy was “shock and awe.” Fred Beteta, who oversaw campaign events, reserved the parking lot outside the convention hotel for an outdoor rally of more than 2,500 people. A high school marching band was brought in to play the campaign theme song, “We’re Not Gonna Take It.” As the convention opened Saturday morning, September 13, the rally began. Delegates looking down from their hotel rooms could not miss it.

For Republicans—or anyone—watching on TV, the rally provided pictures of thousands of people at “the state Republican convention” screaming for Schwarzenegger. The fact that fewer in the crowd were delegates did not matter.

Landon Parvin, the campaign’s speechwriter, had put together Schwarzenegger’s convention address after a long evening on the star’s patio, listening to him talk about his political development. Schwarzenegger had spoken with Parvin about Styria, the Hungarian refugees who escaped communism and arrived in Austria when he was nine, the Soviet tanks he’d seen on family trips to Mürzzuschlag in northern Styria (his home province), his embrace of America’s opportunities, his after-school programs, and the bust of Reagan he had commissioned. After being introduced by Congresswoman Mary Bono, Sonny’s widow, Schwarzenegger began his lunchtime speech.

“Why am I a Republican? I am asked this thirty times a day. And that’s just from Maria!”

“Why am I a Republican?” he said. “I am asked this thirty times a day. And that’s just from Maria!” Schwarzenegger rattled off a list of reasons why he was not only a Republican, but a conservative one at that.

“I’m a conservative because I believe communism is evil and free enterprise is good. I’m a conservative because Milton Friedman is right and Karl Marx was wrong. I’m a conservative because I believe the government serves the people; the people don’t serve the government. I’m a conservative because I believe in balanced budgets, not budget deficits. I’m a conservative because I believe the money that people earn is their money, not the government’s money.”

Each line drew a huge roar. Not one offered a specific policy. But the language was a way of expressing sympathy with conservative ideals without making any pledges. His only promise was to take his bust of Reagan with him to Sacramento.

The real action of the convention came after Schwarzenegger’s speech on the upper floors of the hotel. He had reserved adjoining suites, Rooms 1738 and 1740, as a base of operations from which he could lock down endorsements.

In this peculiar time and place, the fact that Schwarzenegger was not as conservative as conservatives would have liked gave him a special appeal to, of all people, conservatives.

Jon Coupal of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association laid out the strange logic in an email to Shawn Steel, a former state party chair who had worked with Costa to promote the recall: “Supporting Arnold is, in fact, the more principled thing to do. As movement conservatives, endorsing Tom would be easy. It’s what everybody expects us to do. BUT TAKING THE HEAT BY ENDORSING ARNOLD TO KEEP CRUZ OUT IS THE MORE RESPONSIBLE COURSE OF ACTION. In short, I am not about to sacrifice Prop 13 nor my children’s future lives in California on the altar of ideological purity.”

One of the Schwarzenegger team’s main points was that Schwarzenegger, unlike McClintock, could fight and win ballot initiative battles. With Democrats controlling huge majorities in the legislature, any other Republican governor would be hamstrung. “That was the conversation,” said San Francisco talk show host Melanie Morgan. “Arnold could overrule everyone else. He was going to govern by initiative.”

Schwarzenegger eventually went to Executive Suite 1, where more than fifty of the Republican chairmen from California’s fifty-eight counties were meeting. Schwarzenegger’s first two meetings had been warm-ups for this third and most important session. If the chairs went for Schwarzenegger, the infrastructure of the party would follow.

Before Schwarzenegger arrived, the state Republican chairman Duf Sundheim asked for a show of hands. How many of the chairs think Schwarzenegger should drop out and McClintock should be the candidate? Four hands went up. How many think McClintock should drop out and Arnold should be the candidate? More than forty agreed. Many had wanted to back Schwarzenegger, but were too afraid to admit it to their fellow conservatives. Sundheim had revealed the chairmen to each other.

An endorsement would follow. In a single weekend, Schwarzenegger, the Hollywood moderate and perceived novice, had outmaneuvered McClintock, a politician for twenty years.